Sign up to the Brew Mart newsletter for the latest news, offers & more

Wine Making Yeast

Brew Mart has a selection of wine yeasts, for varietal wines such as Burgundy, Champagne, as well as general purpose yeasts, and yeasts specifically for country or fruit wines.

Often wine making yeasts cross over, for example a german style white wine yeast, will also work well with high acid fruits like gooseberry or rhubarb. A burgundy wine making yeast will work well with strong red fruits like elderberry or blackberry and so on. We have a true Sauternes yeast, for fermenting in cooler temperatures, a mead yeast and re-start yeasts. We have a yeast for pretty much everything.

What are wine yeasts?

Yeasts are fascinating. These single-celled organisms are essential to wine, converting sugar to alcohol during fermentation. Single-cell microorganisms are responsible for producing the enzymes that permit fermentation. They convert six-carbon sugar molecules into ethyl alcohol and carbon dioxide while releasing heat.

Yeasts also produce minute amounts of volatile compounds during fermentation, such as esters, aldehydes, and sulphur, contributing to the finished wine's varied aroma and flavour profiles.

As well as creating alcohol wine yeasts also affect the wine's character.

In the world of wine, the king of wine yeasts is Saccharomyces cerevisiae which is favoured because of its

- Ability to thrive in normal wine conditions of pH between 2.8 and 4.

- Predictable and vigorous fermentation capabilities.

- Tolerance of relatively high levels of sulfur dioxide and alcohol

Despite its widespread use, Saccharomyces cerevisiae is rarely the only yeast species involved in fermentation.

Saccharomyces cerevisiae is the same yeast species that causes the dough to rise. It is also known as brewer's yeast because brewers use it to make beer, and bakers use it when leavening bread.

But the one thing that yeast does well is mutating, and there are thousands of cerevisiae strains. All these yeast strains act differently. Consequently, a strain that might be effective or suitable for causing the dough to rise might not be ideal for turning grape sugars into alcohol.

If you tried to inoculate your homemade wine with bread yeast, you'd soon realise that yeast strains have varying tolerances for alcohol.

Bread yeast will typically stop working at about 10 per cent alcohol, lower than most wines. And a tired yeast struggling to ferment can start to create some off-putting flavours and aromas.

Today's winemakers realise what a crucial consideration yeast is

1. It affects how quickly fermentation begins.

2. How rapidly it progresses

3. How the final product tastes.

The amount of yeasts available to home brewers is growing all the time.

How Yeasts affect flavours

Choosing a suitable yeast for the type of wine produced significantly makes red, white or rose.

Yeasts can colour, shape and mould the entire sensual presence.

The fermentation environment, tannins, acidity, and flavour must interplay with the yeast.

- The passion fruit and gooseberry aromas in Sauvignon Blanc can be traced back to elements in the grapes, which are converted into sulphur-containing compounds during fermentation.

- The lychee of Gewürztraminer. The number of monoterpenes released by yeasts is understood to significantly alter the expression of aromatic varieties such as Muscat and Gewürztraminer.

- The strawberry notes of Pinot Noir

- The banana notes of Beaujolais Nouveau are believed to come from the increased formation of isoamyl acetate due to yeast strain 71B.

- Chardonnay's brioche and hazelnut notes are believed to come from the CY3079 yeast.

None of these flavours is found in the grapes, but they are released or created by yeast during fermentation.

It is noted that the influence of yeasts is most prominent in aromatic wines due to the small changes in the concentrations of fundamental components, which affect varietal character' significantly.

Yeasts may continue to contribute to wine flavours even after they have finished working.

When yeasts are allowed to stay in the wine after fermentation is complete, the dead yeast cells start to dissolve due to the enzymes in a process called autolysis.

Some yeast strains ferment slower or faster or work best in specific temperature ranges.

If you're a homebrew winemaker that prefers slow, cool fermentation, you have to pick a yeast that works with your recipe.

Other yeasts have known sensory impacts, bringing spice or floral notes to a wine. Another consideration is how prone a yeast strain is to flocculation, the process by which particles suspended in a liquid clump together and either float or fall out of suspension.

Yeasts that more readily flocculate will produce a relatively clear wine. The wine may remain cloudy or hazy if a yeast strain isn't prone to flocculation.

The Role of Yeast For Wine Making

The action of yeast in winemaking is the most crucial element that distinguishes grape juice from wine.

In the absence of oxygen, the yeast changes the sugars of wine grapes into carbon dioxide and alcohol through fermentation.

The more sugars there are in the grapes, the higher the potential alcohol level of the wine. Sometimes winemakers will stop fermentation early to leave some residual sugars and sweetness in the wine, such as with dessert wines. Stopping fermentation can be achieved by

- Sterile filtering the fermented wine to remove the yeast

- Lowering fermentation temperatures to the point where the yeast is inactive,

- Fortifying with brandy or neutral spirits to kill off any yeast cells.

Sometimes fermentation is unintentionally stopped, such as when the yeasts become exhausted of available nutrients, and the wine has not yet reached dryness. The fermentation is then considered to be stuck.

Harvested grapes are usually teeming with various "wild yeast" from the Kloeckera and Candida genera. These wild yeasts often begin the fermentation process as soon as the grapes are picked. The weight of the grape clusters in the harvest bins crushes the grapes, which then changes into a sugar-rich must.

Secondary fermentation

During Champagne production and many sparkling wines, a second fermentation is required in the bottle, producing the carbonation necessary for the style. A small amount of sugared liquid is added to individual bottles, and the yeast is allowed to convert this to more alcohol and carbon dioxide. The lees are then ricked into the bottle's neck, frozen, and expelled via pressure of the carbonated wine.

Alcohol tolerance

Alcohol tolerance is the level to which a yeast strain can ferment sugars into alcohol before reaching a limit. Certain strains have higher tolerances than others. When choosing a yeast strain, it is essential to ensure that the alcohol level in the finished wine is not greater than the yeast's tolerance.

Factors such as

- temperature,

- nutrients,

- rehydration,

- yeast health

- viability

These will affect the tolerance of the yeast to the level of alcohol production, so there may be some variation in a yeast strains tolerance.

Fermentation temperature range

The fermentation range of a yeast strain is responsible for the temperature at which the yeast will ferment the wine and not stall or become stressed.

If during the wine fermentation it becomes too cold, the yeast will be sluggish or not ferment the sugars.

Too high temperatures during fermentation, the yeast will become stressed and produce undesirable flavours in the must.

Within the temperature range of a yeast strain, there may be some variables that can change. For example, fruity flavours may become more pronounced at the higher end of the temperature range of a particular strain.

When selecting a yeast, the temperature at which the wine fermentation is carried out should be considered.

Attenuation

The attenuation of yeast decides the percentage of sugars a yeast strain can ferment.

80% attenuation would show 80% of the available sugars will be fermented by the yeast.

The attenuation will show how much residual sugar is left in the wine when the yeast have finished the fermentation.

Different yeast strains will have different levels of attenuation.

If you make a sweeter wine, you will choose a yeast with lower attenuation. A lower attenuation means there is some residual sweetness in the finished wine.

Cultured vs Indigenous Wine Yeasts

Some winemakers prefer to use native yeasts (also called wild or indigenous yeasts), which occur naturally in the vineyard or winery, to get a unique expression that some consider more faithful to the wine's terroir or sense of place. But most wine is inoculated with yeast cultures, which can act a little more predictably.

Two of the most controversial subjects in the winemaking realm is

1. Whether to use yeasts naturally present in vineyards and wineries (ambient or 'wild' yeasts)

2. Those manually cultivated to serve specific winemaking needs.

Traditionally, spontaneous fermentation is a combined mixture of naturally existing yeasts.

While the indigenous Saccharomyces species exists on the surface of grape berries, other (non-Saccharomyces), wild yeasts are also present in the environment.

Although they can also impact the quality and flavour of the wine, the wild yeasts tend to give way to the brewer's yeast stain when

- The alcohol strength in the must rises significantly higher than 5% abv,

- There are enough levels of sulphur dioxide to stop their activities.

While there are still discussions about the issue, indigenous yeasts are considered by some winemakers as part of the local terroir. Some believe they give a more balanced and complex flavour profile to a finished wine.

However, naturally existing yeasts always present the risk of unwanted strains – such as Brettanomyces – causing aroma and flavours that some consider undesirable. Equally, wild Saccharomyces yeasts may also be unpredictable and ineffective.

Many modern winemaking operations use pre-selected yeast strains to eliminate such risks and ensure a smoother, more controlled fermentation.

The use of so-called cultured yeast in winemaking 'ranges from 70%-90%' worldwide.

Initially isolated from ambient yeasts, these cultivated strains can vary widely in their characteristics, including the aromas and flavours they promote.

Meaning homebrewers can choose the ideal characteristics they wish to make their wines.

Brew Mart has compiled a list of yeasts for wine making help you understand different yeast strains and varieties and summarised their best uses and characteristics

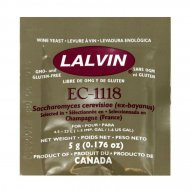

Lalvin EC-1118 Champagne Yeast:

One of the most used and forgiving all-rounder yeast from Lallemand is EC-1118. EC-1118 yeast is recommended for fruit wines because it is a workhorse and will cope with a wide range of conditions and a lack of nutrients.

Robust, Reliable, and Neutral. Valid for various applications, including wine and fruit cider fermentations.

The famous sparkling wine region selects this yeast for its excellent sparkling base wine and "in-bottle" secondary fermentation.

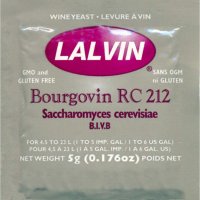

Lalvin RC212 Burgundy Wine Yeast:

Lalvin RC212 is a wine yeast strain isolated in the Burgundy region ideally suited for red wines with structure, colour and tannins.

Lalvin Bourgovin RC212 yeast was selected by the Bureau Interprofessionnel des Vins de Bourgogne and was developed for red wines with colour and structure.

RC212 yeast cells only absorb a specific amount of polyphenols.

The colour of the finished wine is darker and has a higher tannin level, ferments moderately quickly and is a good choice for wines with riper berry and spicy character.

- Alcohol tolerance: 16% ABV

- Temperature range of RC212: 20°C to 30°C (68°F to 86°F)